Prologue

In the early 1950s, Assam stood as a beacon of prosperity in India. Renowned economist Parmeshwar Sarma noted that in 1950-51, Assam's per capita income was higher than the national average by Rs. 50.40. This economic advantage painted a picture of a thriving region, filled with promise and potential.

However, this prosperity was short-lived. Fast forward three decades, and the scenario had dramatically shifted. By the early 1980s, Assam's per capita income had fallen behind the national average by a staggering Rs. 212. This dramatic reversal highlights a story of missed opportunities, socio-economic upheavals, and the complex interplay of local and external forces.

This chapter delves into the intricate fabric of community dynamics and economic transformations in Assam, exploring how the once-prosperous state found itself grappling with growing disenchantment and economic disparity. Insights documented in this chapter are primarily based on the extensive research and writings of Nitin A. Gokhale, a leading strategic affairs analyst and author of The Hot Brew. This piece was originally part of a series of chapters on the marketing of Assam tea with special reference to the Guwahati Tea Auction Centre (GTAC) and the auction system for the book Journey of the Bicentennial Assam Tea Industry, commissioned by the Department of Tea Husbandry & Technology, Assam Agricultural University, to mark the bicentenary of the tea industry in Assam. The tea industry in Assam has crossed a glorious two hundred years since the discovery of indigenous tea plants in the hilly terrains of Sadiya in 1823, marking a turning point in the industry’s history. Readers might find it interesting to explore our previous blog, 'How Tea Was Discovered in Assam,' for further insights.

Introduction

The tea industry stands as India's second-largest employer, supporting over 3.5 million jobs nationwide. In Assam alone, there are approximately 1.2 million permanent workers directly employed in the tea industry, with a notable majority being women. These skilled women excel in the intricate task of tea leaf plucking, showcasing their dexterity and expertise.

To fully grasp the current socio-economic landscape, it's essential to understand the historical context and the policies that shaped the industry.

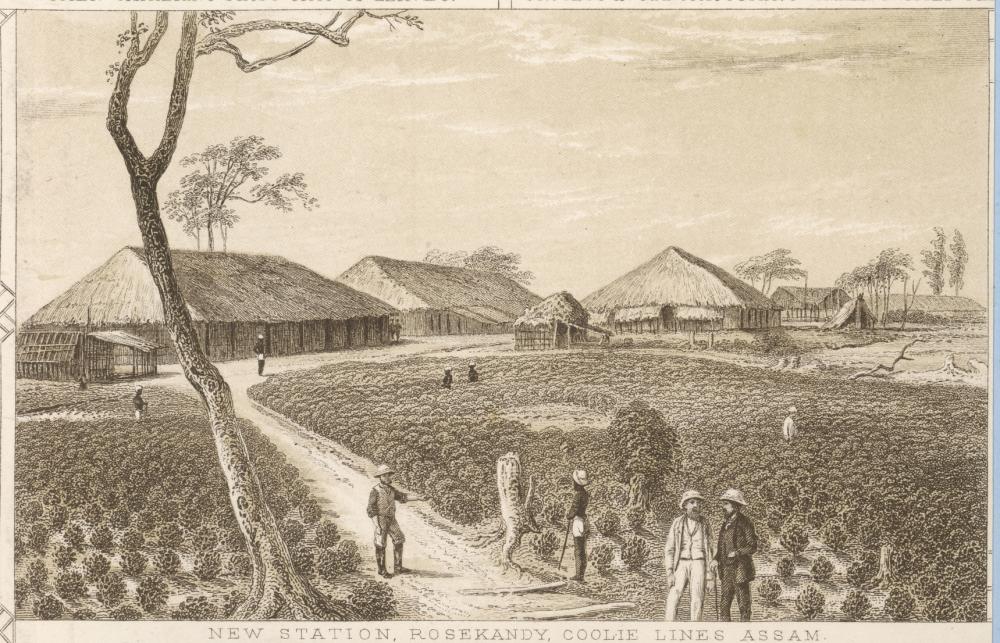

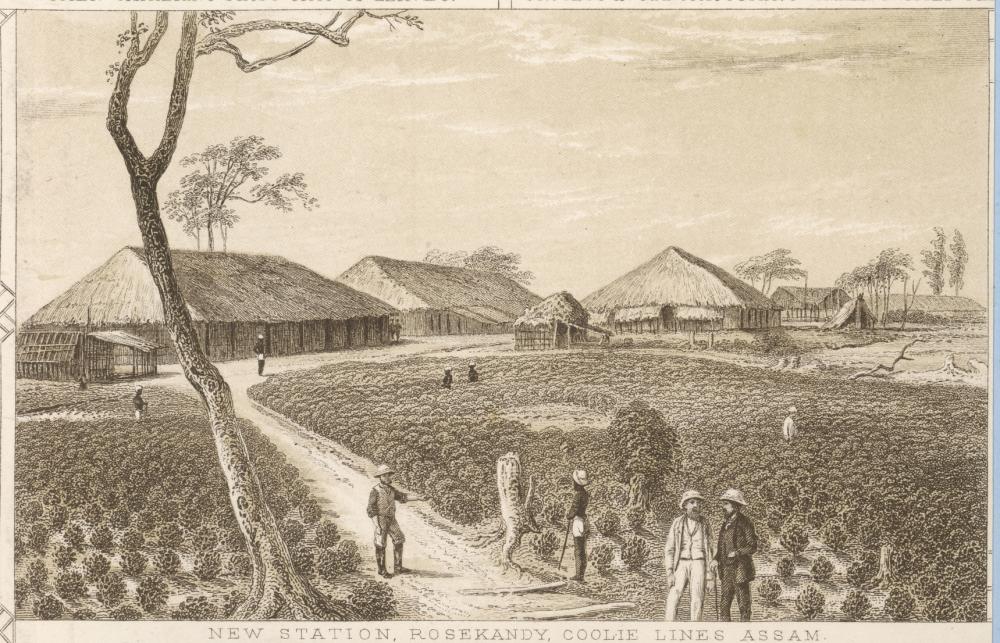

Encouraged by Assam Company's success, private individuals, predominantly Europeans, began flocking to Assam to buy vast tracts of jungle land to set up tea cultivation. To facilitate easy acquisition of land, the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal (who still governed Assam) framed a new set of rules known as the Wasteland Rules of 1838. Under these rules, large tracts of wastelands were offered to applicants on varying conditions. Although locals were not barred from availing the benefits of this scheme,

"rules were apparently framed in a manner so as to exclude them from all concessional grants in practice," (Amalendu Guha, Planter Raj to Swaraj).

No grant was given for agricultural purposes unless the owner possessed at least 100 acres of land or had stock worth Rupees three per acre. These stiff conditions naturally precluded the natives from acquiring land for setting up tea gardens. Perhaps this is where the first seeds of resentment were sown among the locals. They were virtually barred from owning tea gardens by a discriminatory administration.

Yet, there were individuals like Maniram Dutta Barua who braved the odds to set up at least two gardens by the late 1840s. This irked the British planters' lobby, as covered in our previously mentioned blog.

For the next 50 years since 1857, the British did not allow the locals to get into the tea business even as their own commercial enterprises flourished. Records show that by the 1860s, nearly 150 gardens had come up in the state. As tea cultivation spread, there arose a problem of finding sufficient labour, since the whole cultivation process was labour-intensive.

The early planters faced a peculiar problem: the local Assamese, easygoing by nature and agriculturist by profession, were more or less self-sufficient in meeting their own needs. There was no working class worth the name, and so the planters were perpetually short of labour. Attempts to force the locals into tea plantation labour were made by the administration. As Arup Kumar Dutta says in Cha Garam,

"the insidious designs of the European planters, designed to ruin the rural economy and drive the peasants to tea plantations failed to have the desired effect and the local peasantry by and large remained averse to plantation work.”

This forced the planters to import labour from mainland India. Labourers from Telangana, tribals from the heartland of what is now known as Madhya Pradesh and Orissa were coerced, kidnapped, and incited to come to Assam and live and work under appalling conditions. As H.A. Antrobus writes in The History of Assam Company:

“It was agreed in the Board Meeting of June 4, 1839 to offer a Mr. Campbell of Midnapore, a European gentleman well versed in farming pursuits... a job of going to Chota Nagpur or Bagalhpore to collect the families of labourers willing to migrate to Assam. He was to be paid Rs. 2 per head commission for every able-bodied man landed at ‘Works’ (which obviously meant Assam). Rs. 1 for women and children, and for himself Rs. 150 monthly for his own maintenance and for all travelling."

By the end of 1839, the Assam Company had eight Europeans out recruiting. The condition set for them was: they would be taken in as assistants on the tea gardens if they succeeded in getting their batches of labour recruits into Assam. But as Antrobus wrote,

“Recruiting the labour was one thing, but getting them to Assam was always problematical. The supply of boats was not always forthcoming or efficient boatmen who knew the river, whilst sufficient feeding for large numbers at stopping places was not always available.”

As tea cultivation spread, the distance between the native Assamese and the flourishing tea industry progressively increased. Over the years, the chasm only widened, not least because tea companies preferred to remain aloof from the local population once they got a sufficient workforce imported. The initial indifference of the locals slowly turned into resentment, then jealousy, and finally, as we would see in the later chapters, downright hostility.

The Role of Early Planters:

It is easy to blame the pioneer planters for handing down a legacy that attracted charges of aloofness in later years from the locals. In the 1860s and seventies, the early planters, however, had no choice but to behave as they did. As G.M Barker in his 1884 work Tea Planter's Life in Assam, said:

“A manager of a tea garden must be a rather out of the ordinary sort of man. To be of any use, he must be of strict integrity; in order to gain the confidence of his employees, sober, businesslike; a good accountant; not easily ruffled, handy at carpenteering and engineering; know something about soil, have a smattering of information on all subjects; or, to put it concisely, he must be a veritable jack of all trades.”

With so much expected of one person, it was imperative for the planter to be seen as something of a superman. Since he had to be the sole arbitrator on a sprawling tea estate comprising up to 8,000 or more workers, the manager had to lead a lifestyle much different and far more lavish than his labourers.

In short, he had to be the sovereign and the workers his subjects. To be able to live like a monarch, he needed to have a palatial bungalow staffed by up to two dozen servants, waiting to fulfill all his wishes as their command.

Only by instilling fear and grudging respect could the early manager get the work out of his labourers. The work was not easy. In the early years, clearing the wastelands meant hacking vast tracts of jungles to make them fit for tea cultivation.

The hazards were many: wild animals, malaria, and above all, intense loneliness, were the biggest banes of the early planters.

Handling recalcitrant workers was not easy either, language being the biggest barrier. For months together, the sahib perhaps did not see another fellow-European. Means of communication in Assam of the latter half of the 19th century were virtually non-existent. Travel was more often on the back of the elephants or by boats when crossing the innumerable streams and rivers that dot the land. The daily routine could not be more monotonous.

The pretence of being a sahib may no longer be lucrative enough for a new man coming into tea today. The daily routine sans all its British trappings remains as busy and back-breaking as it was centuries ago.

Murgi dak—the first crow of the rooster—begins the burra sahib's day at 6 a.m. Garden time (or 5 am standard, as a tea man is wont to say). Off to the factory, now halfway through its manufacturing shift that began at midnight. After inspecting the quality of tea, and giving instructions for dispatch to various destinations, the sahib comes to his office, where a load of paperwork waits. Chotta sahibs in charge of different divisions, the burra mohuri (accountant), and sundry others have a bichar—the first consultation of the day—in the burra sahib's office about the day-to-day kamjari (tasks assigned to various people).

The bichar is crucial since it involves decisions about a nearly seven-eight thousand-strong population on a medium-sized garden.

The bichar over, the burra sahib just about manages to squeeze time for a late breakfast around 10 a.m. garden time. After spending some minutes with pets and inquiring after his bungalow's servants, he is off to the garden to inspect the plucking. As the sahib appears in the distance, the sirdar (head of a section of workers) starts barking instructions to his team of jugalis (as the workers are known).

The sirdar briefs the sahib about the latest progress and then he carries on. Back at the bungalow, followed by lunch and half an hour of siesta, the sahib is ready to make his afternoon rounds of the garden and the factory. Sunset in Assam is early so plucking stops by 5 p.m. garden time. The workers go home, but the sahib is in his office, planning for the next day, getting accounts up to date, and attending to workers' problems.

Back home, it's time for a quick drink, by himself or with the occupant of the guest room, the faltu kamra, usually a visitor from the company headquarters or a civil servant. An early dinner, and the sahib is about to retire for the day when a jogali from the workers' line comes running, asking for help in attending to a patient. The sahib, not one to shirk his responsibility, rushes to the workers' quarters and renders whatever help he can. By the time he's back in his bungalow, he has just three to four hours to catch up on his sleep before the next murgi dak.

This was then, and is even now, 200 years later, with minor variations, the daily routine of a tea garden manager. He has very little time for interaction with the locals, so caught up is he with the innumerable problems of a normal tea garden.

What added to the insularity of the tea garden population was the fact that the workers on the estates were alien to the locals. Since they had come from far-off places, spoke a different language, and followed different customs, there was nothing common in their lifestyles. Indeed, the locals looked down upon the tea garden workers as a community beneath their contempt.

There was a time when the Assamese youth were reluctant to marry into tea garden workers' families. To the Assamese, the British planters themselves were a distant race, out to make money out of the state's resources, uncaring for the feelings of the locals.

As a result, there was very little interaction between those who lived on the garden premises and those who lived outside it. Distrust between the two communities was inevitable. Even the sahib, not willing to take any risks of his workers hobnobbing with the more enlightened population, lest they got ideas 'inimical' to the company's policies, forbade any contact with the outside world.

As for the sahib, he was lord and master of all he surveyed. Some sadistic managers reveled in humiliating the natives while some others deliberately chose to be insulting to the local population just to keep up the pretense in front of his workers. A couple of examples cited by Dutta in his Cha Garam would be sufficient to shed light on the eccentric and egoistic sahibs. Apparently, a native had to put down an unfurled umbrella if he passed a white sahib, even if it was raining. Another sahib apparently considered it the height of insolence if a native riding a bicycle did not get down when he was passing a European. There were of course some good and honorable men who did a lot to improve the local surroundings and went out of their way to get the best deals for their workers. Through the years, the concept of the manager as mai-baap-sarkar to the entire tea estate population remained constant, though.

Rise and Dominance: Community Dynamics

The company owners had consolidated their properties and had, in time, become very prosperous. Over the years, the tea companies had also evolved a system of welfare measures for the large workforce under which the laborers got subsidized rations, free living quarters, and substantial medical assistance in addition to their wages. Inevitably therefore, the tea laborers began to have surplus cash in hand.

This should have allowed the Assamese peasants to make good profits by selling their produce to the tea garden laborers - but the local, indigenous farmers failed to take advantage of the situation since there were others, mostly immigrants, who proved to be smarter than them. But if the British had their interest only in the tea and oil sectors, the rest of the aspects of the economy in the late 19th and early 20th century were controlled by non-Assamese, mainly Marwaris and immigrant Muslims from East Bengal.

As the immigration increased, the economy also underwent a drastic change. The Assamese, with their laid-back attitude and self-sufficient lifestyle (a kg of rice, a fish for the day, and some vegetables is all that a local needed to be happy, wrote a sahib in one of the numerous memoirs on Assam), were not interested in trade or commerce. As Amelendu Guha wrote:

"... what Assamese completely lacked, however, was an aptitude for commerce.” Unlike the neighboring Khasi people, the Assamese were observed to have been very indifferent to trading occupations.

The Marwaris and Bengalis thus took an opportunity to set up business in the Brahmaputra Valley. In 1874, R.H. Keating, the then Chief Commissioner of Assam, emphasizing the importance of industrial and mercantile communities, pointed out that the Assamese with their subsistence economy were not interested in large trade and industry. Therefore, to facilitate commercial transactions with Bengal, merchants of Marwar were allowed to set up depots at several locations in western Assam.

At the turn of the century, a large number of East Bengal farmers migrated to Assam and occupied the wastelands in the Brahmaputra Valley. They brought in the practice of jute cultivation and made it into a lucrative cash crop. Alongside the cultivation of jute and sugarcane, the more enterprising and hardworking immigrant peasant tapped the considerable resources of the tea gardens laborers by selling them all their requirements: paddy, mustard, pulses, poultry, vegetables, bamboo, etc. The Marwaris, who had by then arrived in Assam and taken over the local trade, benefited immensely from these transactions. In the process, the local Assamese was outsmarted.

All aspects of the local economy gradually went into the hands of the 'outsiders' by the beginning of the century. Amalendu Guha has quoted the 1921 census report in his highly-acclaimed book, Planter - Raj to Swaraj:

"While considerable profits have been made in the tea and other industries, it does not appear that the indigenous population has shared much in these... The rice mills and oil mills of Dibrugarh are owned by Marwaris. A good many of the professional positions are held by Bengalis; wholesale and important retail trade is in the hands of men of Rajputana and of Eastern Bengal; the smaller shops in the villages are kept by upcountry men."

The tea garden owners, of course, made good profits out of the tea business. Even their managers lived in big bungalows, drove around in plush cars, played golf on weekends, attended horse races frequently, and partied in many clubs that came up in different corners of the tea country. The children of the new or 'brown sahibs," as the locals liked to refer to them rather derisively, studied in the best of boarding schools.

In sum, in the eyes of the locals, the tea community had the best of everything. Tea estates came to be regarded as islands of prosperity amidst the sea of poverty. Unseen and unobserved by anybody, a big change was taking place in one respect. The local populace treated tea gardens with a touch of indifference till the time of Independence. As the quality of life deteriorated and the struggle for survival became more intense, the locals began to take a more critical look at the tea estates.

As the population increased and agricultural production failed to keep pace, Assam, which had a large portion of its people self-sufficient in most of their needs till Independence, witnessed the emergence of a dispossessed class. The pressure on land (Assam's density of population is higher than the national average), coupled with lack of investment in the industrial sector, began to tell on the economy.

As the composite state of Assam got fragmented into seven different administrative units, the poverty increased. Unabated migration from other parts of India as well as from across the international border created social tensions. As Anjan Kumar Baruah in his path-breaking study titled Assamese Businessmen says:

"The migrant communities dominated almost all fields in the state.

They included: tribal laborers from the Santhal and Bastar areas of Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Orissa engaged mainly in tea gardens; Bengali Muslims, mainly from East Bengal who settled on land along the Brahmaputra Valley and to a lesser extent, the Surma Valley; Bengali Hindus, originating in East Bengal who settled in Cachar district and throughout the towns of the Brahmaputra Valley where they held middle-class jobs;

Marwaris, an entrepreneurial community from Rajasthan, engaged in trade, commerce, and money-lending and more recently, in a few industries and many tea plantations purchased from the British; a scattering of other migrant communities, such as Nepalis, who have settled in the low-lying hills around the Brahmaputra Valley, tending cattle; Bihar males, who work as seasonal migrants in construction projects and in the towns; and a small but economically significant number of Punjabis working in the transport industry, and more recently in their own business."

Administrative apathy, continuous neglect by the Centre, and a policy of isolation pursued by both New Delhi and its agents in the northeast, added to the economic deterioration of the region in general and Assam in particular. The social environment in Assam was also changing, and agitations and protests were becoming a part of daily life. But the tea industry was still prosperous.

Many boys from the Assamese middle class aspired to become assistant managers and managers of tea gardens. However, due to the lack of quality education and the local boys' perceived incapability for hard work, very few of them entered the tea industry, even as European owners gradually sold off their stock, replaced by Indian owners around the 1960s.

Inevitably, therefore, the tea crowd was a much-envied lot in Assam of the 1960s and 70s. Although recruitment of assistant managers at the local level had gradually begun, most of these boys came from upper-middle-class, convent (read Shillong) educated backgrounds.

Even they, in the eyes of the villagers surrounding large tea estates, were guilty of imitating the sahibs.

As veteran planter and the biggest tea industrialist from a true Assamese stock, Hemen Barooah once said:

"The very lifestyle of the planters practiced by the Europeans and imitated by Indians who joined tea, bred jealousy among the surrounding population simply because even an Indian planter had his food on the dining table, ate with a fork and a knife and moved around in a car. The locals, on the other hand, did nothing of the sort. These two different lifestyles simply created barriers. Ultimately it was jealousy and a sense of frustration among the local people and what they thought was injustice. As a local school master, for instance, would think, 'this planter has two cars and my post-graduate son still goes around on a bicycle,' and things like that went on adding to the jealousy."

Miles and miles of tea gardens spread across the undulating hillocks of the Brahmaputra Valley create an impression of wealth beyond the industry's actual worth. According to GTAC reporting, the combined annual turnover of over 800 tea gardens in the organized sector was approximately Rs. 3300 crores (402.44 million USD) during the financial year 2022-2023, significantly less than the consolidated annual turnover of Tata Group, which stands at approximately Rs. 13,783 crores (1.68 billion USD) with operations in India and international markets.

Vested interests such as politicians and agitators exploited emotions rather than reason, further inflaming latent resentment. In some cases, they grossly exaggerated the industry's turnover and misrepresented it as total profit to unsuspecting populations.

The industry of course contributed to the mis-information and canards by simply refusing to react to the changing social environment. It also added insult to the injured senses of the Assamese by sourcing all its requirements for the gardens from Calcutta.

For the industry it was an easy arrangement since most head and registered offices of the tea companies are located in the West Bengal capital. Since Calcutta still remains the only international trade centre in the East, it makes sense for the tea companies to have their main offices there.

But in Assam the opinion is the exact opposite. Gunin Hazarika, Industries Minister during the AGP government, emphasized that the tea industry could significantly benefit the local economy by sourcing everyday essentials locally. Items like umbrellas, shoes, pesticides, and other necessities, valued back then at approximately Rs. 300 crore annually, could boost Assam's economy if retained within the state.

Meanwhile, the local education system continued to produce a surplus of graduates and post-graduates ill-prepared for practical life, exacerbating youth discontent over limited job prospects. As noted by Myron Weiner in his 1988 book 'Sons of the Soil,' educated Assamese youths faced barriers in urban employment sectors dominated by migrants. He highlighted that migrants outnumbered locals in sectors such as manufacturing, construction, trade, commerce, and transportation. In contrast, local Assamese were less likely to secure non-agricultural jobs, despite more local representation in state government roles, which included a majority of Bengali Hindus born in Assam.

To return to the subject of tea companies being aloof from the local populace, it was inevitable. Most companies were London-based and run by British executives who often made decisions based on reports from head offices in Calcutta or telegraphic information from the tea estates. These decisions primarily focused on shareholder interests.

The tea industry, the most visible symbol of affluence, haughtiness, and higher social grade, thus became the target of collective ire among local youths. This resentment intensified with the rise and dominance of migrant communities in commerce and industry, highlighting their disproportionate benefits from Assam's resources and opportunities.

The silent time bomb, ticking away since the late seventies, finally exploded nearly a decade later and when it did, it caught the captains of the tea industry by total surprise. This critical period, exploring the socio-political landscape from 1987 to 1997, is documented in another upcoming chapter. Stay tuned for its release!

Leave a Comment